Suspending temporary releases of imprisoned people is penal populism, argues president of H360 in an interview

The following interview, conducted by journalist Valéria França, was originally published in Portuguese in Veja magazine on March 1, 2024.

With the largest prison population in its history, more than 830 thousand prisoners, the Brazilian prison system has major problems, such as overcrowding, lack of operational infrastructure and organized crime. Despite the complex problems, Brazilian legislators have dedicated themselves in recent months to another issue that does not bring effective changes to the penitentiary system, nor does it actually increase the safety of the population: changing the temporary release regime for prisoners – the popular “saidinha”, a right granted only to those sentenced in a semi-open regime. It allows criminals to visit their family, study and even participate in social integration activities, five times a year, without State surveillance. On February 20, the Senate approved PL 2,253/2022, which suspends this prerogative. The bill had 62 votes in favor, two against and one abstention.

Presented by deputy Pedro Paulo (PSD-RJ), initially the project repealed the Penal Execution Law (Law 7,210, of 1984). When it reached the Senate, the total suspension of the right was reverted to partial, through an amendment approved by Senator Sergio Moro (União – PR). Exits were maintained only for prisoners enrolled in vocational courses or in secondary and higher education for the necessary duration of the activities and exits on holidays were suspended. Lawmakers claim that many criminals do not return to prison after their escape, which, according to them, increases insecurity in society. PL 2,,253/2022 returned to the Chamber of Deputies and then goes to presidential approval.

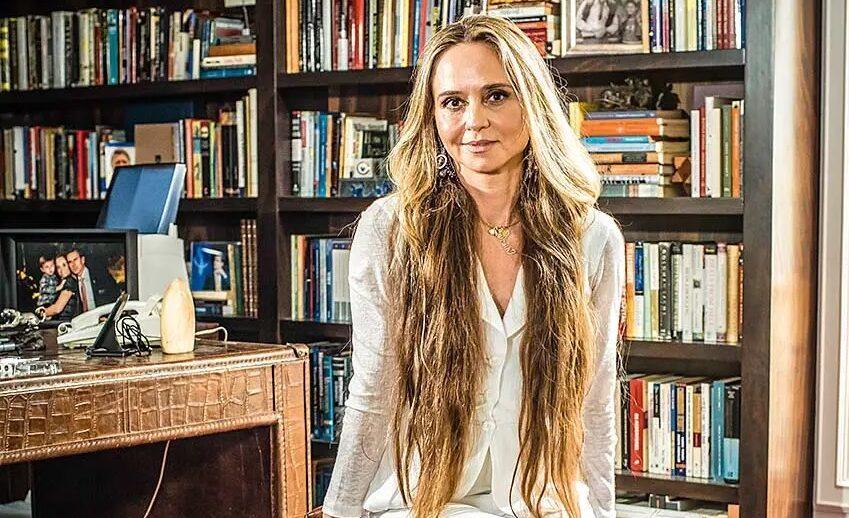

The senators’ decision caused a lot of controversy, as it was seen as a setback in the rights of this population. There was no lack of criticism regarding the justification for not returning to the outings. “This rate is low, less than 5% of prisoners do not return to prison”, counters lawyer Patrícia Villela Marino, founder of Instituto Humanitas360, a non-governmental organization that works with the rehabilitation of prisoners. In an interview with VEJA on the topic, she draws attention to the suspension of a right provided for by law, important in resocialization, which will harm the majority of inmates who follow the rules by returning to prisons after being released. Below, the chat with Patrícia, who is among many who do not agree with the Senate’s decision.

Do you see the release of prisoners on commemorative dates as a privilege or a right?

Temporary releases are a right, not a privilege, and are provided for in the Brazilian Criminal Execution Law as a resocialization mechanism. Contrary to popular belief, releases can only be authorized for people imprisoned in a semi-open regime and subject to a series of criteria, such as minimum time served and good behavior. Temporary release is an instrument that prepares the person to leave prison, allowing them to reestablish or strengthen family and community ties, to begin or resume studies and to seek professional training.

How does it work in other countries?

With differences in the form of application and the criteria required, the temporary release also exists in other countries, such as the UK, Spain, Italy, Portugal and France. It is also important to say that regime progression and the existence of resocialization mechanisms are not exclusive to Brazilian legislation, being widely adopted by other nations.

Is the rate of non-return of prisoners as high as the senators claim? What is it like in other

countries?

As Rafael Velasco, former national secretary of Penal Policies under minister Flávio Dino, recalled, the percentage of less than 5% of people arrested in Brazil who do not return after leaving is low. It turns out that the small successful missions of these people who leave temporarily to visit their family, study and work do not receive the same attention from society as the violent exceptions, which are regrettable and must be closely monitored, so that they do not happen again. but which are – it is important to emphasize this – exceptions.

What did you think of the Senate’s position in approving the cancellation of prisoner releases?

It is yet another demonstration of penal populism. Without having concrete answers to the public security crisis, some of the congressmen – in this case, unfortunately, the majority – prefer to ignore the data, turn their backs on the experts and dispense with the frank debate with society to offer an easy, spectacular and misleading response to a problem that requires a systemic and complex look. Betting on the closed regime as a solution to the problem of violence and crime in Brazil is turning a blind eye to what happens in our prisons today. The more obstacles legislators create for the resocialization of imprisoned people, the more they are pushing this population back to a life of crime.

You have a great deal of experience with women in prison due to your social work at Humanitas360. Can you tell me how the news has reverberated among these women? What do they say?

From the work we have developed at the Humanitas360 Institute in recent years, I draw the conclusion that in the Brazilian prison system there is a majority of people looking for a second chance. It turns out that their individual will is not enough. To restart their lives with autonomy and away from crime, the State and organized civil society must actively contribute to building alternatives, undoing prejudices and, step by step, returning this person to social life in a dignified way, with access to education, health and work. See the number of people deprived of their liberty in Brazil. Now imagine how many are ex-prisoners. Think about the number of family members affected by this reality. We are talking about millions of people. It’s a problem that concerns everyone.

What would be the most appropriate measure for a situation like the country is experiencing, where prisoners escape from high security prisons and with a high degree of public security being compromised by organized crime coordinated within prisons?

The crisis in Brazilian public security requires a systemic look at its causes. Mass incarceration, overcrowding in prisons and the restriction of resocialization mechanisms form the perfect conditions to make prisons a kind of “school of crime”, where criminal factions are born and recruit new members. Doubling down on this repressive logic will not solve the problem, but feed it. The logic of public security lies in intelligence, not repression. Furthermore, it is urgent to discuss a review of the Brazilian Drug Law, a path towards which the Federal Supreme Court seems to point with the judgment regarding the possession of Cannabis for personal use. Brazilian congressmen need to abandon the search for short-term political dividends and mature the debate on these issues. Otherwise, we won’t face the problem head on.